Art to Encounter View All →

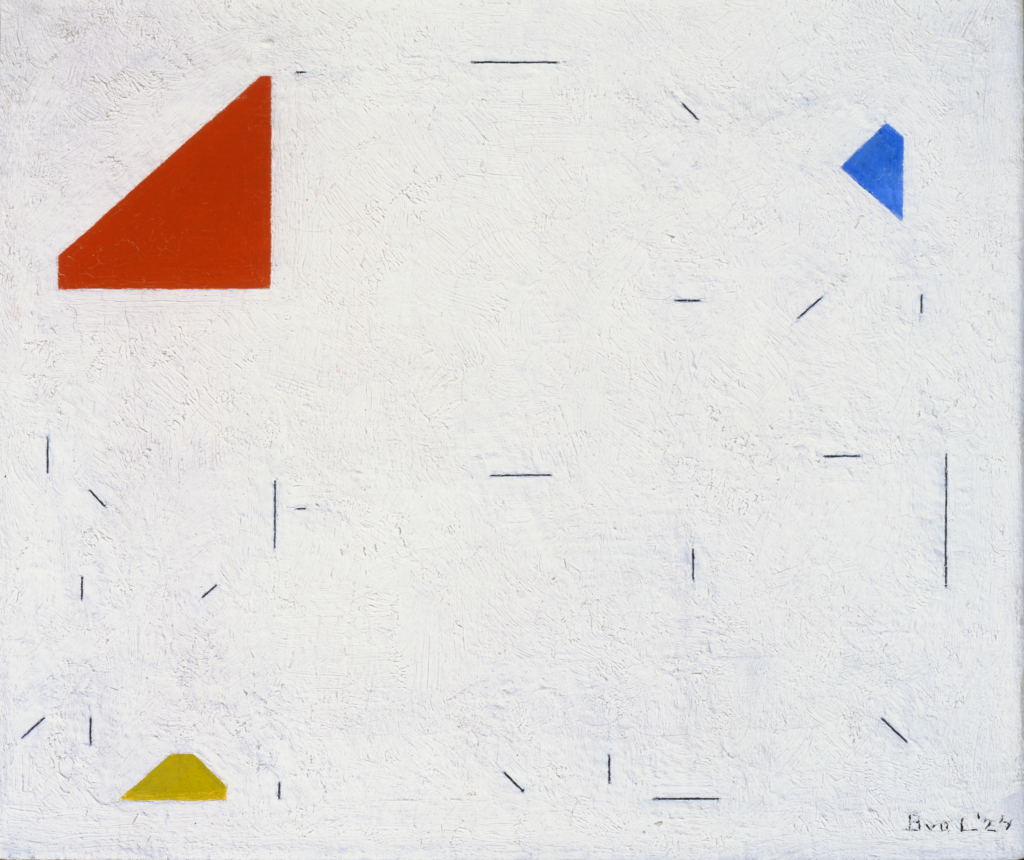

On view through May 12, 2024

On view through July 21, 2024

On view through Sept. 22, 2024

On view Through Jan. 26, 2025

Skip the Line 🎟 Get Your Tickets Now 🎟

What’s Happening View All →

Sat., Apr. 20, 11 a.m.

Sun., Apr. 21, 2 p.m.

Wed., Apr. 24, 9 a.m.

Thurs., Apr. 25, 4 p.m.

Ways to Learn

Visit our online resource library to read, watch, and listen!

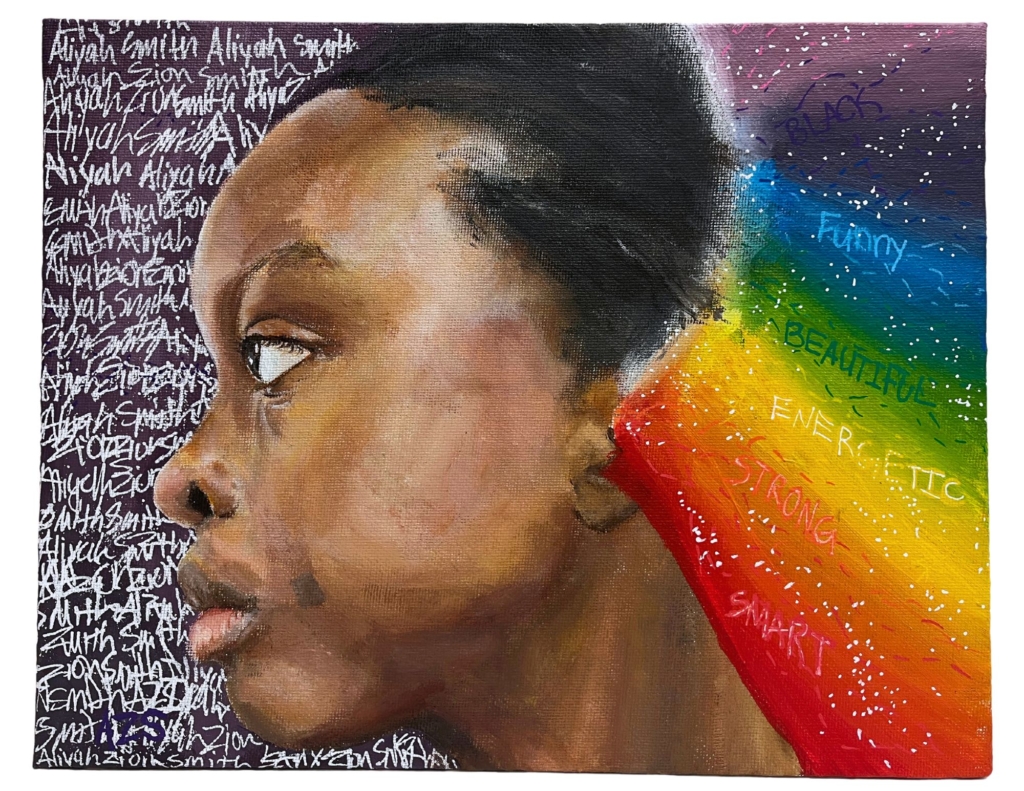

The created language emerges from the depths of each metal surface.

Art in Your Inbox 📧 Sign Up For Our Newsletter 📧